What Made Me

What Made Me

Words / Cody Liska

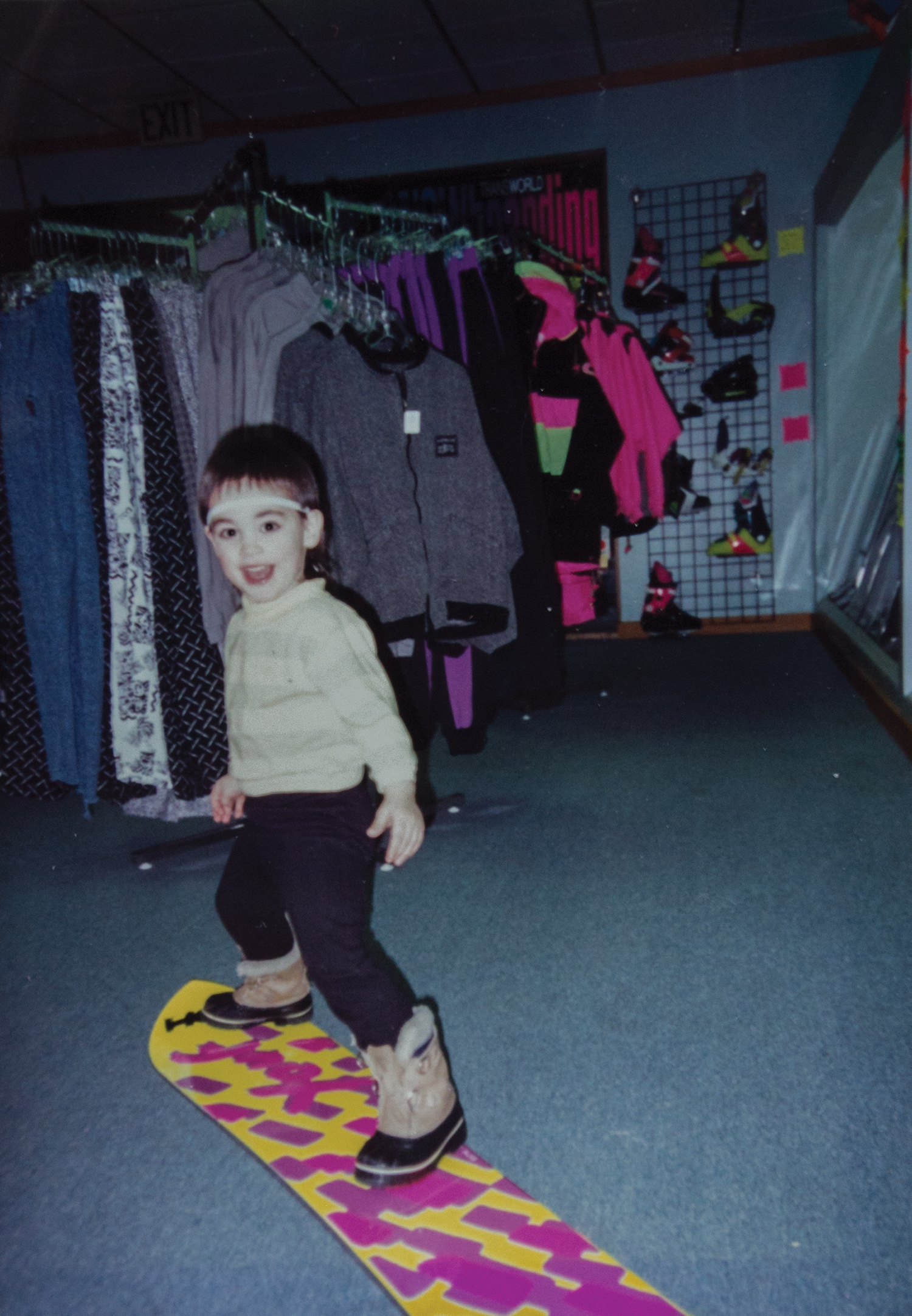

Photos / Sharon & Scott Liska, Ryan Earp

The last thing I remember was my dad telling me to put my seatbelt on because we might hit a cow. It was 2000 and we were on our way to Mammoth Lakes, California for Nationals, driving i395 through Death Valley – a stretch of road known as “Blood Alley” because of the high number of vehicle-related deaths. We were listening to the first Terror Squad album, In For Life. I had a Dr. Pepper and a Flintstone Push-Up. Those are all the details I remember from that night. The next thing I remember was muffled sounds, unfamiliar voices and being pushed down a long, bright hallway.

“13-year-old Caucasian male, fractured femur, cranial trauma,” an unknown voice analyzed as I tried to focus my eyes and my attention. But it never happened because sedation kicked in.

I would be in surgery for the next three hours. In that time, sterilized medical utensils sliced at my battered body in an attempt to mend wounds. Doctors and nurses worked to ensure my 13-year-old bones would properly mature.

After surgery, I was returned to a room I had unknowingly occupied for days. There my mom embraced me as much as she could, considering my condition. She pressed her cheek snug to mine and wrapped her arms around me with enough slack for comfort.

“What happened,” I asked.

“You and your dad were in a bad car accident,” she choked up. My grandma Lynn had been the one to tell her the news. Lynn drove to my parents’ house the night of the accident and, silhouetted by the porch light, told my mom what had happened. To hear her tell it, my mom instantly knew something was wrong. She opened the door and, upon hearing the news, collapsed right there in the entryway. She was on the next flight from Anchorage to San Bernardino, praying the whole way there.

Doctors said the collision was equivalent to hitting a brick wall at 160 mph. After my dad regained consciousness, he exited the driver seat, ran to the passenger side of the vehicle and, realizing the door was too smashed to open, began punching the window until it broke. He attempted to pull me out of the broken window, but I was pinned. The dashboard of our rental had interrupted my right leg just below the pelvis, causing my femur to snap in two. It would take the Jaws of Life to get me out of the mangled wreckage. And it would take a helicopter to medevac me to the nearest hospital to save my life. My dad would have to find his own ride to wherever they took me. And since he wasn’t told where that was, he hitched a ride with a truck driver and guessed.

Later, my mom would tell me the outcome of the oncoming truck that hit us: “The other vehicle that hit you… the driver, he was drunk, he lived; the man in the passenger seat died on impact and the man in the back broke his neck.”

All that happened 5 days ago. Now, I was in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit at Loma Linda in San Bernardino. I was fresh out of surgery and a nurse was removing my catheter. And, as my parents were leaving the room, I remember my dad saying, “you might want to just leave it in, it makes it look bigger.” I stopped laughing when I felt the pressure and a burning sensation of the catheter tube being pulled out my urethra.

I was a patient at Loma Linda for three weeks. When I was admitted, I was put into a medical-induced coma to keep my brain from bleeding and swelling – the crash had caused a frontal lobe petechial hemorrhage. The doctors talked about drilling a burr hole in my skull to release the pressure, but the swelling subsided. Protuberances of skin filled with shards of glass lined the inside of my forearm. My knees were banged up and my femur broken. My right leg was put into traction – a metal wire was threaded through a hole in my leg just above the knee.

“They couldn’t take you into surgery when you were admitted because you were unconscious,” my mom said with tears pouring down her cheeks.

It was hard for me to consider myself a snowboarder after that. Broken bones didn’t bother me much because I’d broken bones before. I knew they would heal. It was my head injury that bothered me. My Cognitive Therapist told me, flat out, that I could never snowboard again. When I told my dad, he said, “fuck him.” And so that was the mentality I adopted. I would still snowboard because what other choice did I have? From as far back as I can remember that’s what I’ve done. To give it up, I thought, would mean a complete loss of identity. I mean, most every formative experience of my life has been underlined by snowboarding.

I met all of my oldest friends through snowboarding. I met Gus Engle on my first chairlift ride at Hilltop Ski Area in Anchorage. “Hey, my name’s Cody. My dad owns Boarderline.” No shit, those were the first words I ever said to Gus and I’ve never been able to live them down. Gus introduced me to Sunny Forshee and Clayton Linden. Sunny introduced me to Sebastian Garber and Eric and Adam Eldred. Adam introduced me to Bryant Burgin. The list goes on. If it wasn’t a shred buddy introducing me to a new one, then I met people through Boarderline. Matt Eastman, Jake Randazzo, Mark Thompson, Christian Koch, Ant Black, Ryan Sturgeon. That list goes on as well. Without Boarderline, or more specifically my dad, I would have never met Sandy Spitzer at Windell’s Snowboard Camp. I worked at Windell’s every summer for about 6 years and Sandy was my “Camp Mom.” She was, and still is, the shit. In fact, everyone would always joke about how Windell’s should be renamed “Spitzer’s” because, without her, that camp would’ve shit the bed.

The first beer I ever drank was during Boarderline Camp, at a party at Sammy Luebke's house – the double A-frame; the one that looked like Madonna’s tits. I got blackout wasted. As a sort of punishment, Justin Kellerby aka Killabee, deadhorsed my leg black and blue because, although I was allowed to snowboard with the boys, I wasn’t allowed to party with them. I think that was the same year we would steal cigarettes from Sammy’s mom and smoke them under the bridge by Glacier Creek. That was the same year Sammy and I got our first shots in a JB Deuce video. Sammy was like 8 and I was like 9. We did backflips off this side-hit in the Glacier Bowl. Jason Borgstede filmed it.

The last Boarderline Camp is still so fresh in my mind that it feels like it just ended. Sunny and I decided that, in order to avoid drinking and driving, we'd ride bikes that summer. Problem was, we didn't own a bike. What we did have were pieces of bikes – a tire here, a set of handlebars there. So, we pieced together this rickety, Frankenstein bike and that's what we would ride. At least that’s what we thought. It lasted one trip around Girdwood and that was it. We rode this shitty bike from our tent in the back parking lot of the Prince Hotel – now known as the Hotel Alyeska – down that winding sidewalk that leads to the town of Girdwood. I sat on the handlebars and Sunny steered. Sunny wore two backpacks, both filled with beer. As we soon realized, two 18-year-olds weighted down by a case of beer can really get moving. We bobbed and weaved along that sidewalk, continuing to pick up speed. Faster and faster we went. At about terminal velocity, I turned my head and suggested that maybe we slow down a bit. "Brakes are out," Sunny yells over the passing trees and whizzing tire tread. I was acutely aware of the wobbling front tire, mainly because it was too small for the frame. We narrowly ate shit and then shotgunned a beer or 5 in celebration. That was in 2005. In 2010, Sunny passed away as a result of a work-related accident.

In 2006, Boarderline went tits up. When that happened, the whole infrastructure crumbled, fracturing the Alaskan snowboard and skateboard community. Zumiez was at the center of the debacle. The Wal-Mart of snow and skate shops came in and took a steamy dump all over our community. Everyone knows it. People are just scared to openly acknowledge it. To this day, Zumiez has never once even sponsored a skateboard or snowboard event in the state of Alaska. “Because no one has ever approached us about it,” I’ve heard of a Zumiez manager saying. “Well, fuck you,” that’s what I say. If you sit around waiting for somebody else to do your job, then it’s never gonna get done.

I’ve spent a lot of time hating Alaska for what it is and what it isn’t. Silently loathing all of these local brands that insist upon the novelty of Alaska rather than representing it in a genuine way. There’s an infestation of biters and sellouts here and, for some reason, people support them. It’s the same self-destructive support that drives mom and pops to bankruptcy; it’s the same mentality that drives Alaskans to grand openings of chain restaurants in droves, squirting their pants over Olive Garden when Sorrento’s – a local Italian spot with much better food – has been around since the 70’s. A Long John Silver’s opened in Anchorage a few years back and there was a line at the drive-thru that wrapped around the entire building, to the point where it almost reconnected with itself. I don’t know what kind of person lives in Alaska and chooses to eat processed fish, but evidently they’re out there. However, I think it’s too dismissive to write these people off as impressionable and meek. I think the answer is much simpler and more human than that. More than anything, I think it has to do with inclusion. Like, we subconsciously think that by opening up a national chain is some grand gesture into the larger culture that is the United States. Every time I think about it, I picture that old Anchorage Daily Times’ headline announcing Alaska’s statehood: “We’re In.” Because that’s what a lot of people up here want, they want to be included, to be “in.” It makes sense. Nobody wants to be excluded.

It really is a magical thing when we find that place of belonging. But when that place is taken from us, we become discouraged and jaded, and then eventually, pessimistic and resentful. I know because that’s how I’ve felt for a very long time. “Just don’t fuckin’ think about it,” my dad would tell me. But it’s hard not to think about something you care so much about. To be able to give this next generation of snowboarders and skateboarders the same thing I grew up with would be huge. I hate to think that I grew up during a time that may never exist again. I’m sure other people hate it too. How could they not? It was the Golden Era of the Alaska snow and skate scene. There was a competition series, a snowboard camp, a skatepark, and it all revolved around a shop that gave a shit. But overall, there was a sense of community. And we took it for granted. I think it's actually better that way though, to take it as it comes and live in the present. And then, years down the line, let nostalgia set in. Not too much though because nostalgia can be dangerous. Reminisce for too long and you remain in the past.

Tragedy has a particular way of putting things into perspective. In the wake of loss, you tend to focus on what’s actually important, rather than superficial nonsense. You realize that relationships and, by extension, community are the only things that really matter. Not your job or your house or your clothes or your car or that one party you went to – none of that matters. Because when you’re laying on your deathbed, you’re not gonna be thinking about how cool that EDM DJ’s set was. You’ll be thinking about all the people in your life. All your family, friends, and loved ones. You’ll be thinking about how you met those people and all the memories you share. You’ll be thinking about those formative years that were so important to your identity.

So, you wanna know how I know I’m still a snowboarder? Because, on sleepless nights, I close my eyes and envision riding up Chair 6 at Alyeska. I pass South Face cat track on the left, Half Moon and Horseshoe are further up the mountain to my right. And then, near the top, I look left toward Kitchen Wall cat track. It’s always a pow day and all my friends are there. This vision replays again and again until my breathing shallows and I start to doze. And whatever’s keeping me up at night fades away and all that’s left is a feeling. It’s a feeling of content, but more importantly it’s a feeling of belonging. This is where I’m comfortable because these are my roots.

"What Made Me" originally appeared in Crude Issue 04. Check out Issue 04 / Legacy here: crudemag.com/buy-crude/legacy04